Building batteries and bridges

Thursday 14 June 2012

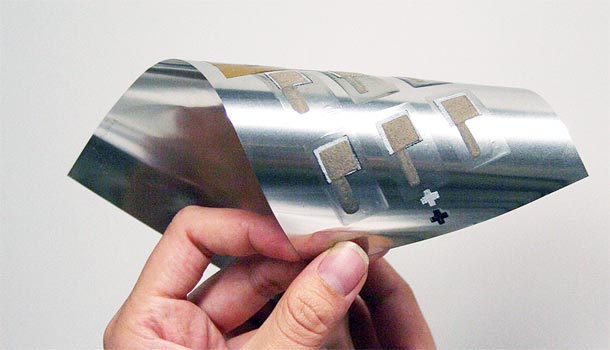

With moral and monetary support, including a UC Proof of Concept Grant, two UC grads have formed a company to create 'printable' batteries that are efficient, environmentally friendly and could be made as small as a postage stamp.

If you want to get a recent Ph.D. on the phone, it’s usually not too hard. Just call down to a post-doc laboratory and ask for the person who hasn’t been outside in two weeks.

Christine Ho, however, is tougher to catch. Perhaps that’s because as co-founder of a startup called Imprint Energy, she is traveling between meetings with potential investors and her new laboratory and manufacturing bay. Ho is that rare creature – a student inventor who managed to bridge a great idea into a fledgling company.

It all began in 2007, when she took a break from her Ph.D. at UC Berkeley for a three-month fellowship in Japan. Since her undergraduate years, she had been working on a project funded by the California Energy Commission (through the Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society, or CITRIS) to develop tiny wireless sensors to make buildings more energy efficient. Her focus was a new type of tiny battery that would be easy to make and reduce the negative impact batteries tend to have on the environment. The problem was that standard lithium-ion batteries are made from rare Earth materials. Plus, they've been known to explode in one's laptop.

So, she went to Japan for a fresh perspective. However, the lab she was in had neither tools nor the money for lithium-ion battery work. So she changed course.

“We decided to look at zinc technology, which is the oldest type battery chemistry you can think of,” she said. “A majority of our cheap, disposable batteries are made of zinc.”

Brooks Kincaid and Christine Ho, recent UC Berkeley graduate students, co-founded a company to make printable batteries.

In the battery world, a scientist using zinc is like a car manufacturer investigating horse-drawn carriages. Zinc batteries are fine for cheap throwaways, but today’s market is all about rechargeables and you can’t recharge zinc.

Perhaps because zinc had been so ignored, Ho found it was ripe for revolutionary thinking. The reason zinc batteries cannot be recharged is that inside their watery acid chambers they form ugly cone-shaped dendrites on the metal electrodes. Eventually, these growths prevent the battery from working.

“I had a very negative view of zinc batteries prior to Christine’s work. And so does the rest of the world,” said Jim Evans, a UC Berkeley electrochemist and Ho’s advisor. “The zinc electrodes deteriorate over time. You may start off with nice flat zinc and before too long it develops holes and dendrites and all kinds of nastiness.”

Yet Ho realized that zinc is (a) plentiful, (b) environmentally benign and (c) not prone to explosions. The only problem was the dendrites. But, she reasoned, if you can’t change the zinc, why not change the electrolyte? She replaced the battery’s liquid with a polymer film — similar to plastic but far more conductive — and eventually created a new zinc battery.

When she went to recharge it, not only did it work, but it worked again and again — more than 200 times. Better yet, because it didn’t have any dangerous chemicals to house, it could be as small as she wanted. Better still, she could build them with little more than an ink printer.

In most research stories, this would be the end. Ho would get a pat on the back, a Ph.D. and a few lovely papers recommending further research. The gap between innovative research in the university and products that serve society is so wide it's often called “The Valley of Death.” Every year, countless brilliant ideas are lost because there is no mechanism to bring them into the market.

But that’s not what happened to Ho’s “printable” batteries. Moral and monetary support — including contest prize dollars and a significant grant from the UC Office of the President — juiced her battery project,

With encouragement from the California Energy Commission and CITRIS, she met with a few potential investors and enrolled in a class in the Haas Business School called Clean Tech to Market. The class paired promising inventors with business, law and engineering students to discover go-to-market strategies. One of her partners was a MBA student, Brooks Kincaid, who coincidentally had gone to high school with her.

After the class ended, the pair got back together and decided to enter her batteries in a Berkeley Venture Lab competition put on by the College of Engineering’s Center for Entrepreneurship & Technology.

“We got $7,500,” she said. “That wasn’t a lot in the grand scheme of things, but it was a lot to us at the time. It just got the ball rolling. We thought, ‘Maybe we can really do this.’”

They entered more competitions like the UC Berkeley Business Plan Competition (where they won in the Energy track) and even a global entrepreneurship competition. By 2011, they had raised $75,000, and so they started Imprint Energy.

With the help of another advisor, professor and manufacturing specialist Paul Wright, she and Kincaid devised a way to manufacture batteries the size of postage stamps, using the same technology to pattern silkscreen T-shirts.

“It’s like a multi-deck sandwich,” said Wright. “In the printing industry, in magazines, to get all the colors to line up when you are doing multistage printing, that is very difficult. It’s the same thing for this kind of manufacturing.”

In fall of 2011, a $250,000 award to Evans from UC’s Proof of Concept Commercialization Gap grant program provided the critical funding to cross the “Valley of Death” and show that their battery was commercially viable.

With the grant, they were able to conduct the research that would increase manufacturing capability from eight batteries a day to more than a 100 a day. They also addressed ways to make production of the batteries safer for workers and less hazardous to equipment and consumers. Quickly, their idea indeed developed into something marketable and potentially valuable to society.

Thanks to the many UC programs to help entrepreneurs get started, Imprint Energy is in business — literally. They have hired five people and look to bring in a few more by September. They have solid seed money from what Ho calls “a large chemical company” and have moved off campus to their own facility in Alameda.

In April, at a forum in which UC Proof of Concept program grantees presented their innovations to industry and technology venture capitalists and government agency representatives, Ho was a hit. After her presentation, she met with several people interested in the new batteries.

Ho said the transition from university to actual markets is tough. Originally she imagined her printable batteries in tiny wireless devices. But in the real world, she and Kincaid have to narrow down an existing market and specific existing customers within that. She said that never would have happened without all the support she got. In many ways, Imprint Energy is not just a new type of battery but also a new type of bridge — one that spans the Valley of Death.

“There is this phrase, ‘If you invented a better mousetrap the world would beat a path to your door,’” said Evans. “And I think that is sheer nonsense. It may never have been true. It’s always necessary for people who come up with these great discoveries to work very hard to interest people in investing, becoming customers, even just to take the idea seriously. So, no, the world does not beat a path to your door.”