New strategies pinpoint breast cancer risk, spare many from agony

Tuesday 5 February 2013

With the help of donations from state tax filers, the California Breast Cancer Research Program funds innovative research. Studies have led to simple tests that guide treatment by distinguishing non-invasive forms of the cancer from aggressive types.

Every year, a small lump in the breast or a suspect speck on a mammogram leads 40,000 women in the U.S. to a diagnosis of the most common form of non-invasive cancer.

The condition — ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS — is most often harmless. The pre-cancer cells are usually confined to breast milk ducts and lie dormant, posing no threat. But 15 percent of DCIS cases give rise to invasive cancer and, until now, oncologists had no way to tell one from the other.

As a result, women with DCIS have had two basic options: Wait and hope that the condition won’t advance to an aggressive cancer, or choose to treat it now as a potential life threat.

The second choice leads to a full or partial mastectomy, often followed by radiotherapy or hormone treatment. Whatever the decision, it comes with heightened anxiety. And those who choose treatment face pain, discomfort and often high medical costs — all for a condition that only leads to cancer about one time out of five.

In 2007, after 10 years of research, a team of UCSF scientists developed the first simple test that may spare about half of the women diagnosed with DCIS from aggressive treatment. The test looks for telltale proteins, or biomarkers, in breast tissue that indicate that the breast cells are responding abnormally to stress.

“For the first time, we identified the patients who have the lowest risk and the group at highest risk of developing invasive cancer,” says Thea Tlsty, Ph.D., a UCSF professor of pathology whose basic cancer research underlies the success. She and her colleague, Karla Kerlikowske, M.D., professor of medicine, are advancing this biomarker strategy to large clinical trials in several sites within the U.S and abroad.

“This would not have been possible without combining our expertise in both basic and clinical research,” Tlsty said.

With support from the UC’s California Breast Cancer Research Program and the state’s tax checkoff which allows tax filers to donate to cancer research, the two scientists are working to extend the current biomarker signature to parse those at higher risk for metastasis. They hope to more precisely distinguish within this higher-risk group which women will need aggressive treatment and which may worry less.

Like the initial test, the extended signature will search for evidence of abnormal cell behavior. But it doesn’t look for changes caused by mutations as most biomarker tests do. Rather, it screens for changes within cells caused by molecules that attach themselves to proteins.

Like the first test, these so-called “epigenetic markers” also reflect a cell’s response to stress. Research suggests that these changes too can identify DCIS that will advance to invasive cancer or to metastatic growth beyond the source tumor. Tlsty and Kerlikowske hope this screen can be accurate enough to identify women with DCIS that are most at risk for metastasis.

“The CBCRP is very unique and powerful because it seeks out promising areas that are underappreciated and develops them,” Tlsty said.

“If a woman is diagnosed with DCIS, she is usually treated as if she has cancer, even though more than three-fourths of them won’t get cancer,” said Tlsty. “Think of all the exposure to drugs and hormone therapy for these women who don’t need it.

“If we can demonstrate the value of this new biomarker signature, we can advance to national-scale trials supported by the National Institutes of Health, and soon may be able to allay the fears of tens of thousands of women a year. This is very exciting.”

Saliva test

Another CBCRP-funded innovation in breast cancer screening will look for biomarkers in human saliva — just about the least invasive way to access genetic material.

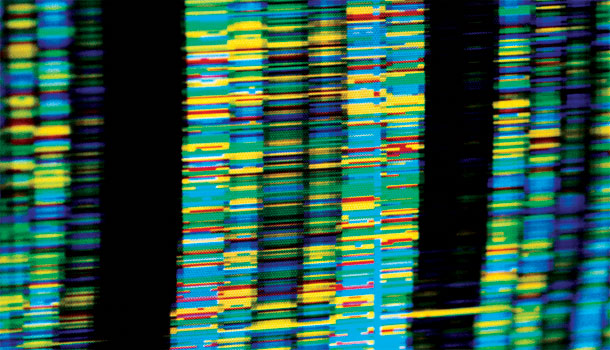

Lei Zhang, a researcher in the Section of Oral Biology at the UCLA School of Dentistry, is devising a test for two forms of ductal carcinoma. Before seeking CBCRP support, his group developed panels of biomarkers in saliva to detect pancreatic and lung cancer using the laboratory workhorse of DNA and RNA screening technology called a microarray. This powerful and widely used strategy allows researchers to compare snippets of patients’ DNA or RNA with similar genetic material in healthy people. Where the gene sequences or gene expression levels differ can be a clue to a cause of disease.

But Zhang wants to move from detecting partial genes to actually sequencing entire genes using a state-of-the-art technology called “Next Generation Sequencing” (NGS), an approach that promises more accuracy.

One of the commercially-developed screening tools he will use offers major advantages over microarray approaches. It detects panels of cancer-related genes very quickly, is easy to employ and provides the needed genetic evidence at low cost.

It might seem odd that genetic changes in saliva cells could indicate that a tumor is developing in the breast, but that’s what Zhang’s research has started to show.

“We hypothesize that all molecules of the body are affected by primary tumor. The tumors will stimulate changes in DNA and RNA throughout the body.”

He suspects that using the new sequencing approach to screen for cancers will significantly boost accuracy, and reduce both the time and cost needed to get results.

“CBCRP has funded our studies at exactly the right time because we were really struggling to develop novel and accurate biomarkers based on NGS,” Zhang said. “We needed support to push the research and evaluate its effectiveness.”

Zhang hopes the funding will advance the new strategy to the point where the National Cancer Institute will support large-scale clinical trials. He expects NGS will be available for breast cancer diagnosis in clinics within five years.

Zhang feels grateful for the willingness — even eagerness — of breast cancer survivors to participate in the studies, providing saliva samples needed to confirm the tests’ effectiveness.

“I have been very touched by the many survivors who want to support this work. They have suffered, and they want new research to benefit other women.”

See also: