Digging the ancient Maya

Monday 17 September 2012

UC Riverside archaeologists are leaders in studying the mysterious Maya world, a dominant culture many centuries ago.

Two thousand years ago, they built dazzling cities deep in the unforgiving jungle. They invented the concept of zero long before Europe. They calculated dates thousands of years in the future, and their understanding of the stars would make Galileo jealous.

And though they did not predict the end of the world, the ancient Maya provide us with some of the most compelling mysteries in anthropology. For many, the ancient Maya are the last frontier of true explorer archaeology.

Unlike in ancient Rome, Bactria or Egypt, scientists have only discovered a fraction of the material that exists from this once-dominant culture. And what’s left is buried under centuries of neglect and perhaps more than a few layers of topsoil.

At the cutting edge of the effort to understand this civilization sit three eminent Mayanists in the anthropology department of UC Riverside.

Among them, Karl Taube, Wendy Ashmore and Scott Fedick have perused as deeply into the Maya world as any people on Earth, teasing apart the Maya world from the sacred to the mundane temporal.

“It’s the best Maya anthropology program in the country,” says department chair Tom Patterson. “You have three world-renowned Maya archeologists in the same building.”

Corn and death

The first is Taube, the iconographer. In contrast to epigraphy, the direct translation of inscriptions, iconography tries to understand the themes behind ancient writing. While an epigrapher might dissect a particular Latin phrase, an iconographer would consider sweeping ideas such as the image of the cross in ancient Rome.

Taube’s specialties are maize and the afterlife. By looking across cultures spanning from the Olmecs — who preceded the Maya — to the Hopi in the American Southwest, Taube revolutionized our understanding of the role of corn in ancient Mesoamerican culture. He has traced maize gods through one civilization after another to document their central role and how they change. Currently, he is using these ideas to tease out the links between the Maya and the Olmecs through a fantastic set of murals discovered in the early Maya ruin of San Bartolo in northern Guatemala.

He also spends a lot of time thinking about death: specifically, whether the Maya had an alternative to Xibalba, the “place of fear.” After being tricked into death, the Maya believed that most people went to a dark and miserable underworld to suffer into oblivion. But Taube has found that an alternative place existed — a “celestial paradise related to the sun, flowers, music” designated for royalty.

“I think it’s very clear now that for the classic Maya, kings didn’t want to live forever in the crappy underworld, but in the heavens, right? In the world of the sun,” he said.

This may seem like a simple task, but intuiting the ideas of long-dead civilizations is tricky work. Then, as today, much of the meaning in a piece of text was inferred by the reader from their knowledge of popular culture. Nowhere was this more acute than in Taube’s favorite site, Teotihuacán. Just outside Mexico City, the pictorial writing in Teotihuacán was so obtuse no one even knew it was writing until recently, when Taube and others started to read it by interpreting several repeating images. This is in stark contrast to the Maya script, which forms words as you would see in English.

“It would be like comparing Greek writing to Chinese writing. The Chinese writing is strongly logographic — that you don’t have to be able to speak Chinese to read it,” Taube said.

Architecture, how they lived

Alongside Taube in the department is Wendy Ashmore, whose work takes a step away from ethereal world of gods and the afterlife and looks at where Maya people lived and worked.

“It started from looking at the arrangements of a particular settlement where I worked for my dissertation,” she said. “And it just incited a whole bunch of questions in me. Why is this there? Why is the front of the building facing this way? What did people do inside?”

What came out of those questions was what some loosely call the “Ashmore Template” — a set of principles governing the positioning of buildings reflecting the Maya worldview. For instance, the Maya often equated south with death and the underworld, and north with royalty and everlasting life. As a result, when you stand in a plaza oriented to the four cardinal directions, there is a good chance the northern end will house the royal dead while the southern end will house relics tied to the non-royal dead.

Her career thus has grown out of the intersection between architecture and economics, politics and religion, finding meaning in how people lived and went through their days. A coarse way to describe it would be a Maya version of feng shui.

“Some people have made that explicit comparison,” she said. “I don’t necessarily think that. But I do think that the orientation of buildings and the location of activities is shaped by beliefs about the world and the universe.”

Understanding common folk

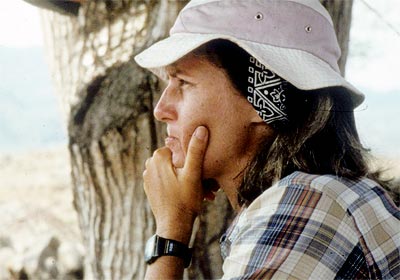

The third of the UC Riverside Mayanist triumvirate is Scott Fedick, whose work takes even more steps away from the realm of the gods to the profane world of, quite literally, the Earth.

“The questions that I am trying to answer are how the Maya managed to feed themselves over a very long period of time with what appears to be a very large population,” Fedick said. “I kind of look at the 99 percent of the population. I don’t work very much with the elite, the kings and such. I do archaeology of the commons.”

Rather than looking at individual sites, Fedick takes a regional approach, analyzing how Maya farmers dispersed themselves across landscapes. The standard view of Maya farming is a sort of slash-and-burn style, rotating crops from one nutrient-poor plot to the next, with the jungle filling in behind them.

But Fedick objects to this picture of the Maya lowlands as a hostile, uniform place. Fedick and his students have found evidence of intensive agricultural practices like including terracing, wetland cultivation and even fertilizers in home gardens. In addition, he has compiled a list of 500 food plants that the Maya would have used to supplement their diets beyond just maize.

“Although corn was certainly a very important crop to them, both as a food source and a symbolic plant,” he said, “they had 499 other food plants that they could also use.”

For 20 years, Fedick has taken undergraduates to the jungles of the Yucatan to map and excavate ancient Maya sites, spawning both new information as well as many enthusiastic young archeologists. The project was funded through research grants and more than $300,000 in private donations, a testament to how captivating Maya archaeology is to the general public. Sadly, recent budget constraints have mandated larger class sizes, forcing him to end the field class.

But that hasn’t slowed Fedick down much, and these days he is gearing up to identify new sites with a laser-based technology capable of mapping vast areas of the jungle floor from an airplane or helicopter.

It’s this kind of work, all three scientists say, that you can do when you concentrate talent in one place. Patterson says that UC Riverside has a special interest in Latin America, thus making Maya studies a natural fit. For the scientists, they are just happy to have access to the kinds of discoveries that push our understanding further.

“I came to UC Riverside because of the expertise in the department,” said Ashmore. “It’s always exciting for me to find out about new stuff. And it’s cropping up all the time. New insights come from every time you look at a site plan, the descriptions of places and the archeological data that comes in.”

Photos:

Top: A detail from a sacred Maya mural at San Bartolo — the earliest known Maya painting, depicting the birth of the cosmos and the divine right of a king. Photo by Kenneth Garrett, National Geographic.

Wendy Ashmore. Photo by Jan Beatty.

Scott Fedick conducting research in the wetlands of northern Quintana Roo, Mexico. © Copyright Macduff Everton 2012.