A haven for the spooky and the geeky

Thursday 27 October 2011

With more than 100,000 books, the Eaton Collection at UC Riverside is the world’s largest public assortment of science fiction, fantasy, horror and utopian literature. And it is a valuable resource for scholars and researchers worldwide.

The old black and white photograph shows a precise-featured man wearing glasses, a puckish expression and a keffiyeh, headgear straight out of the costume chest of Lawrence of Arabia. The pipe in his mouth only adds to the incongruity. Was he dressed for Halloween? A costume party?

Whatever the occasion, it’s hard to avoid the impression that the late J. Lloyd Eaton having a grand old time.

J. Lloyd Eaton

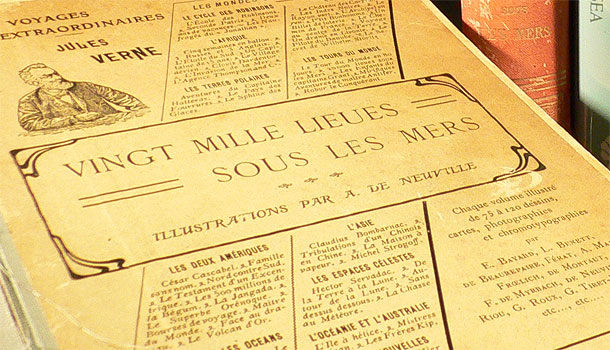

Eaton, a UC Berkeley alumnus and a doctor in Oakland, Calif., was an avid collector of science fiction, fantasy, horror and utopian books. But when Eaton wanted to donate his collection of some 7,500 books in 1969, even iconic authors such as Jules Verne weren’t regarded as “serious.” Eaton tried several universities before UC Riverside accepted his donation.

In hindsight, this acquisition looks remarkably prescient. Today those genres are taken very seriously indeed. Authors of the first rank, such as John Updike, Margaret Atwood and Haruki Murakami, have written books about time travel and dystopian futures. Science fiction has grown from a nerd’s hobby to a meditation on the nature of existence.

“The 20th century, when science fiction emerges and becomes popular, is the century when science and technology becomes absolutely central in everyone’s life,” said Rob Latham, a UC Riverside English professor. “It’s a literature that helps people understand the future shock they’re living through.”

Over the past 40 years, the Eaton Collection has become the world’s largest publicly accessible collection of science fiction, fantasy, horror and utopian literature, and it’s a valuable resource for scholars and researchers worldwide. Its 100,000 books include a much-prized 1517 edition of Thomas More’s “Utopia” and first editions of “Dracula” and “Frankenstein.” The collection also includes 90,000 fanzines, the amateur magazines published by science fiction aficionados.

The top names in science fiction, including Ray Bradbury. Samuel R. Delany, Harlan Ellison, Frederik Pohl, Robert Silverberg, Theodore Sturgeon and Roger Zelazny have attended Eaton conferences at UC Riverside. So have leading mainstream literary critics such as Leslie Fiedler and Harold Bloom.

In its October 2011 issue, Wired magazine ranked the Eaton Collection No. 2 on its list of global “Geeky Destinations and Smart Side Trips.”

The accolade in Wired recognized the often-overlooked connection between technological innovation and science fiction, said Nalo Hopkinson, a Jamaican-born writer of science fiction and fantasy who joined UC Riverside’s creative writing faculty this fall.

Hopkinson pointed out that Bill Gates and Paul Allen, the co-founders of Microsoft, were science fiction buffs. British newspaper columnist Damien Walter recently reported that Chinese authorities have encouraged the popularity of science fiction, hoping to foster U.S.-style innovation. But the Chinese authorities got more than they bargained for when author Chen Guanzhong came up with a cogent political critique in his novel “The Prosperous Time: China 2013.”

Science fiction has been a powerful tool for social commentary since the days of “Gulliver’s Travels,” according to Hopkinson.

“Science fiction and fantasy wrestle with the clash of cultures, with the way humans change the world around them, and who does the dirty work,” she said.

Partly because of its usefulness as social criticism, science fiction has always been an international literary form. Some feel it has a special role in the U.S., where the naturalistic novel dominates literature. Science fiction and other imaginative genres have flourished as a kind of guilty pleasure since the 1960s, when Cold War fears were expressed by novels and popular television series such as "Star Trek."

In a society where it is increasingly difficult for people to delve into the unconscious or acknowledge their fears, films like “The Matrix” give us places to put “all that our civilization represses and oppresses,” according to the British film critic and horror buff Robert Paul Wood.

Melissa Conway, the Eaton collection’s director, is a Dante scholar with a Ph.D. in medieval studies from Yale. She sees the role of fantasy and science fiction as profound.

“The old image of science fiction is long gone,” she says. “When I came here, I started seeing the links between science fiction and fantasy and medieval literature. Medieval Christianity offered a structure so the inscrutable pain of life could be put into a meaningful framework. That’s what religion does best. In its own way, science fiction does this, too.”

In recent years, increasing numbers of students have been drawn to UC Riverside because of the university’s reputation as a place where imaginative literature is valued. In addition to Latham and Hopkinson, the campus hopes to add a third professor who specializes in media: film, games, and visual culture.

Riverside already is a magnet for students interested in the field, particularly since Hopkinson’s arrival. Her work has earned praise from mainstream sources such as the New York Times, which listed her second novel, “Midnight Robber,” as a notable book in 2000. But Hopkinson remembers that when she approached another university where she wanted to study creative writing, she was told that the program didn’t teach “genre” writing.

“It’s just as easy to have rigorous content and rich fiction in any genre,” she said. "All fiction is, to some extent, fantasy. You make it the hell up.”

It’s hard not to think that in an alternate universe somewhere, J. Lloyd Eaton is chuckling.

(Large photo at top of page is by Vlasta Radan, UC Riverside Special Collections and Archives)