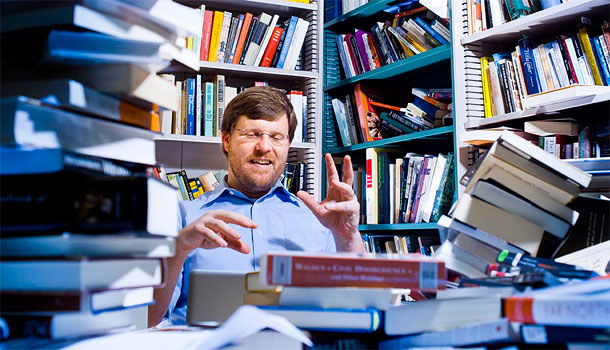

Michael Ziser

Literature, Environmental Humanities and Ecocriticism

Davis

Michael Ziser is a rising star in the growing field of ecocriticism, which examines the relationship between literature and the physical environment.

For Ziser — a UC Davis associate professor of English and director of the Environmental Humanities Supercluster — ecocriticism offers a lens through which to examine virtually any kind of text, including material normally associated with history, post-colonial studies, agriculture, even popular culture.

As a Harvard graduate student, Ziser looked at how people wrote about nature before the invention of “nature writing” with its emphasis on the Romantic tradition of lyrical paeans to solitude among the birds and bees. He mined accounts of early explorers of the New World in the 1500s, including farmers more concerned with draining swamps than waxing poetic about them. His goal was to understand a time when nature was a force to be reckoned with rather than a passive object to be “saved.”

“He’s a forthright and outspoken guy,” says Lawrence Buell, professor of American literature at Harvard. He helped establish the field of ecocriticism in the 1990s and mentored Ziser when he was a graduate student. “I’m in his cheering section,” said Buell.

Recently, Ziser has begun to write about another practical aspect of American life: oil.

According to Ziser, our culture’s investment in oil is not just material, but symbolic. He hopes that if we recognize the power of oil as a symbol, we just might be able to separate myth from reality, and make more sensible decisions about our energy future.

Question:

Anyone who's filled their gas tank recently thinks that something is wrong with our energy policy. But there is a lot of disagreement about the solution. How does culture influence the debate?

Answer:

I did a talk recently about oil. I went back to the idea of what it is to be a member of the white male middle class in the U.S. Benjamin Franklin said this is someone who commands the labor of others. This male role was twinned with energy very early on, when oil came on the scene in the late 19th century.

I unearthed a 1902 text called “Sketches in Crude Oil,” an early history of oil in the U.S. The author has all these bizarre descriptions in which African Americans are reacting gleefully to the advent of oil, a form of energy that is going to potentially release them from being the energy.

As you go into the 20th century, you have this strong identification of middle class, especially white males, with the combustion engine. Muscle cars are the obvious example.

Question:

How does this translate to energy policy?

Answer:

The contemporary manifestation of these national myths are the people, especially in the Rust Belt, who refuse to believe in the science of climate change. One of the big climate change deniers in Congress is Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wisconsin) from the suburbs of Milwaukee. The Harley Davidson plant is in his district. It’s a manufacturing-heavy district that’s also wealthy and white.

You wonder why you can beat your head against the wall and still not convince somebody. It’s very deeply ingrained. It’s part of someone’s identity.

Question:

This is the subject of your new book project?

Answer:

Right. It will launch from “Moby Dick,” at the very end of the whale oil regime, and then I’ll go through the various oil cultures. I’ll touch on Upton Sinclair’s novel.

Question:

Titled, aptly enough, Oil.

Answer:

Right. The oil shocks of the 1970s engendered responses in art, imaginative responses to the world we were about to enter. Those works are a repository of a previous generation’s thinking. The movie that preceded “Road Warrior,” “Mad Max,” has oil shock written all over it.

Question:

Both fine post-apocalyptic movies. Apocalypse is a perennially popular scenario, but how realistic is it?

Answer:

Apocalypse is an avoidance mechanism. But apocalypse is so compelling! There’s a reason why “The Day After Tomorrow” and “Waterworld” were produced. The challenge is figuring out the aesthetic is of a non-apocalyptic environmental writing while not downplaying the seriousness of environmental issues.

Question:

So how does someone tell the story of climate change in an intellectually honest way?

Answer:

In academia there’s a sense that climate change is a problem unlike other problems. It doesn’t fit into traditional narrative models, so we need very avant-garde forms.

I disagree, mostly on pragmatic grounds. Climate change really is about cultural change. There are large powerful interests competing for subsidies to take over the next energy regime, so you can’t confine yourself to the avant garde.

Question:

One of the criticisms of the environmental movement is that it's a white, middle-class-dominated movement. There have been attempts to reach out, but they haven't always been successful. How does one go about addressing the disconnect?

Answer:

I’m still haunted by one student. One of our assignments was to talk about a more or less natural environment. This student was a first-generation immigrant who grew up in an apartment. She had literally never been to a state park or some kind of public land.

We have a number of students whose parents are Hmong immigrants. They come from the mountains and they’re resettled in these flat hot places. They have these amazing gardens that they’ve recreated from Thailand or Cambodia.

The students have grown up with Mom’s “weird” herb garden and her “strange” medicines. But they’re distancing from it, not seeing it as part of their future, and instead seeing it as part of their past. When I show interest as their teacher, sometimes they can see the value in it, and recognize that it’s a truly interesting thing.

I hope they’ll think twice about abandoning it.