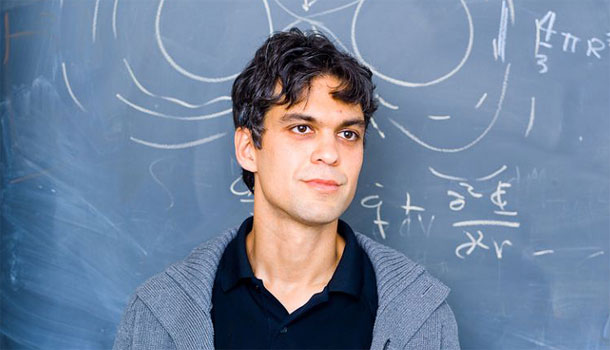

Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz

Astronomy and Astrophysics

Santa Cruz

At some universities, English majors fulfill their science requirement by taking a version of “Physics for Poets.” This isn’t as whimsical or as easy as it sounds. Physics deals with fundamental ideas about time, space and matter — questions as relevant to poets as they are to mathematicians.

Physicists tend to be polymaths, so it’s not entirely surprising that Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz, UC Santa Cruz professor of astronomy and astrophysics, cites the short story “The Library of Babel” by the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges as his inspiration. Borges played with notions of time and space, so it’s easy to see the attraction to a budding physicist. And like Borges, Ramirez-Ruiz can fairly be called a wunderkind.

Ramirez-Ruiz uses computer simulations to explore violent phenomena such as stellar explosions, gamma-ray bursts and the accretion of material onto black holes and neutron stars. At 35, Ramirez-Ruiz is the youngest person to be inducted into the Mexican Academy of Sciences. Since joining the UC Santa Cruz faculty in 2007, he has earned numerous awards including a Packard Fellowship and a National Science Foundation CAREER Award.

“Enrico is working on some of the most difficult and interesting and challenging areas in astrophysics,” said Neil Gehrels, chief of NASA’s Astroparticle Physics Laboratory. “He’s already internationally recognized. As a physicist, you have to develop a reputation, get funding and establish a research group at a major university. Enrico has done all these things at breakneck speed.”

If the accolades bring to mind a brilliant misfit, a la Russell Crowe in “A Brilliant Mind,” think again. Ramirez-Ruiz is entertaining, down-to-earth and thoughtful about the lives of people who are neither physicists nor poets. And, yes, he is rock-star handsome.

Question:

What kind of school did you go to when growing up in Mexico City?

Answer:

My maternal grandparents left Spain during the Franco era, because of the Spanish civil war, and I went to an active Montessori-like school set up by some of their fellow immigrants. These Spanish immigrants revolutionized education in Mexico. The place was very open-minded. No tests. Letting your spirit thrive. It was a great school.

Question:

What did your parents do?

Answer:

My mom is a biochemist. My father is a chemical engineer. They work at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

Question:

How did you get interested in physics?

Answer:

I always liked math and I was interested in gravity when I was very young. I was mesmerized by physics, and struck by the fact that you can actually describe nature by using simple mathematical rules. I was drawn by Newtonian mechanics, because they’re beautiful and elegant.

Question:

E.O. Wilson, the Harvard conservation biologist, said he expects physicists to answer that oh-so-nagging question about the existence of God. Do ultimate questions drive you?

Answer:

Physicists are taught to be very skeptical about everything. We always embrace doubt. It’s the pleasure of not knowing that drives us, drives the curiosity forward.

Question:

Someone noted that you have been very good at choosing research topics, and this has helped propel your career. Was this conscious or did one question lead to another?

Answer:

My advisor at Cambridge was Martin Rees, an astrophysicist who is Astronomer Royal and served as president of the Royal Society. He taught me that when you do astronomical observations, you’re decoding reality, so you have to be very, very careful. If you’re an observer, if you get one thing wrong or are sloppy, you’re finished. But if you work in theory, and get one prediction right, you’ll be famous. So if you want your work to have an impact, you need a vision of the questions that are going to get answered soon.

I’m working on extending our knowledge of cataclysmic events. A lot of this research couldn’t have been done before because we didn’t have the technology. In this era of celestial cinematography, we go back to the same piece of the sky every week or every month and assemble very dynamic images, such as a star getting ripped apart by a black hole.

There are fundamental changes in how we see the universe lately. We’re seeing the movie script of the universe.

Question:

What is the most exciting thing you are working on?

Answer:

The thing that excites me the most is the detection of gravitational waves. This will be one of the main breakthroughs, seeing deformations of space and time.

Question:

It sounds like one of those Hollywood time travel movies.

Answer:

Everything that moves, even us, produces these deformations of space and time.

The waves from the Earth-sun system are minuscule, but we can point to other sources. Neutron stars, for example, are the densest objects in the universe. They’re formed when a massive star collapses. A neutron star can have the mass of the sun but be only the size of Manhattan, about 10 kilometers. When neutron stars collide and merge, they generate substantial gravitational waves. As waves of gravitational radiation pass a distant observer, that observer will find spacetime distorted by the effects of strain. Distances between free objects will increase and decrease rhythmically as the wave passes.

It’s a very rare occurrence but we sometimes find them in pairs orbiting around each other. They go in their own dance, their own waltz. As they spiral closer, the waves become more intense. At some point they become so intense that it should be possible to detect their effect on objects on Earth or in space.

Think of it this way: If you have a blanket and you put a stone on that blanket, and there are ripples around it, you can think of that blanket as space and time. A planet deforms space and time. A neutron star does this more dramatically.

Question:

Do you see physics everywhere? When your son throws you a ball?

Answer:

Not all the time. But I do sometimes think about it. I see someone surfing and I think about what it takes to move someone a certain speed.

I definitely try to make associations. People talk about metaphors in writing, but I think scientists tend to work in metaphors. Newton thought about why the Earth goes around the sun, and drew an analogy to how things fall. Creativity in physics is partly based on your ability to draw from analogies.

Question:

It is fascinating that you work with the Royal Astronomer and also with kids of farmworkers. You started the Lamat Program, a way for students from Hartnell College in Salinas to research with you and your team of graduate students each summer. And you have used part of your research funding to allow a Mexican student to study here for eight weeks each summer.

Answer:

A university education in Mexico is completely free. When you have that kind of opportunity you are conscientious about giving back to the society that invested in you.